Johnny Page saw something as a child that no young person should ever see.

“I witnessed my cousin being killed when I was maybe six, seven-years-old,” he said. Page said he was traumatized by the experience. He said he was overcome by a need to protect his family and friends. He became a fighter.

Page grew up in a low-income area of Chicago. He joined a gang when he was about 11 years old. He sold drugs, got arrested, and he was shot. But even while his life outside school was tumultuous, Page said he was always a good student. He had a reputation for being a smart kid.

Then, at 18 years old, his life took a turn for the worse. Page was convicted of murder and sentenced to more than two decades in prison in 1992. It wasn’t until 2009 that he heard about a new college in prison program called the Education Justice Project. The program brought University of Illinois classes to Danville Correctional Center — a medium security, all male prison with about 1,700 inmates in east central Illinois.

Page said he was initially skeptical of the program.

“When EJP first came I wasn’t really like ‘oh yeah, that’s dope let’s do it.’ I was like you should go to the community and spend some of that money and stop some kid from ending up like Johnny. That was my attitude,” he said.

‘We need a way to measure our success’

EJP is one of an estimated 200 college in prison programs nationwide. Since 2009, more than 220 incarcerated people have taken U of I classes through the program. But there’s a growing debate over how to measure the success of programs like EJP beyond how many students are released and return to prison.

By the time EJP came to Danville Correctional Center, Page said he had exhausted the educational opportunities available to him in the Illinois prison system. He already had an associate’s degree at that point, and he said he enrolled in EJP because he wanted to continue his education.

“Honestly, I just wanted as much information as I could possibly have because I felt like I was sitting in a cell because (there) was information I didn’t have. There were some gaps,” Page said.

EJP students can’t earn a bachelor’s degree, but they can transfer the credits they receive in the program toward a degree at a college or university once they’re released. The program is funded by the U of I, grants and individual donations.

This spring marks the program’s 10-year anniversary. The milestone also coincides with an existential turning point for EJP.

“We need a way to measure our success,” said Rebecca Ginsburg, the director of EJP and a professor at the U of I.

“I’m saying that because many of the people who are saying we have a way to measure our success are, in my opinion, wrongheaded,” she said. “And that way is typically through measuring recidivism of students who have completed the program.”

Ginsburg said the value of higher education in prison programs is generally boiled down to one single data point: recidivism. In other words, whether the student returns to prison after they’re released.

“There’s a tension between the way many college and prison programs view the work that we do and the departments of corrections nationally view the work that we do,” she said. Ginsburg said college in prison programs shouldn’t be measured solely through the lens of recidivism.

EJP recently received a $1 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. A portion of the money is being used to fund a three-year evaluation of the program. Ginsburg said the goal is to figure out how EJP can measure its success through both qualitative and quantitative data.

Nicole Robinson, of NNR Evaluation, Planning and Research in Wisconsin, was hired to head that effort. Robinson said it’s difficult to get prison staff and policymakers to care about measures that aren’t recidivism.

“What I anticipate to be hard and what already feels hard is that this work could be perceived as completely irrelevant,” she said.

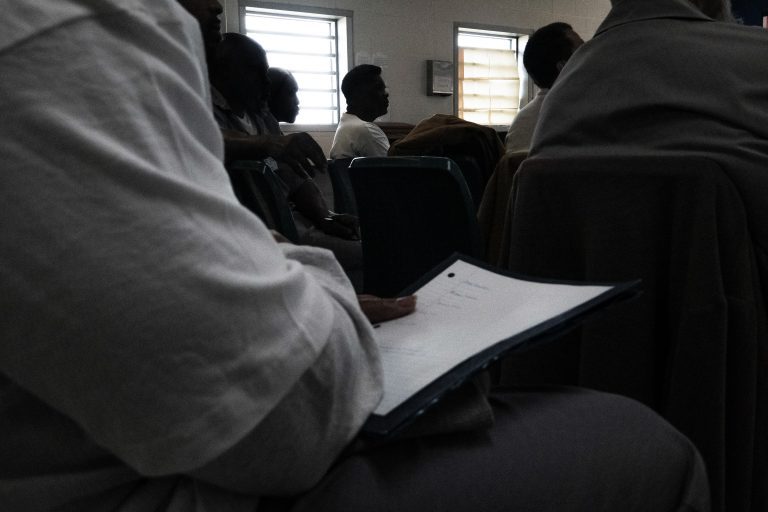

Incarcerated men at the Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Bonne Terre, Mo. listen to a panel presentation hosted by the St. Louis University Prison Program on March 21, 2019.

‘A collective sense of frustration’

Roughly 5% of EJP students return to prison after they’re released, though Ginsburg said that number is based on a limited amount of data. Statewide, 43% of people convicted of felony offenses will return to prison within three years of their release, according to data from the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council.

Research points to a connection between education and recidivism. A 2013 study from the Rand Corporation found that people who participate in prison education programs are 43% less likely to return to prison.

But that study bothers Mary Gould, the interim director of the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison — a group that advocates for the expansion of higher education in prisons nationwide.

“It requires programs to say, ‘here are our recidivism statistics,’ because it put in the minds of everyone in the public and policymakers and researchers and folks in the (department of corrections) that really the outcome is recidivism.”

Gould said there’s a “collective sense of frustration around this question of recidivism in the higher education in prison community.” She said the metric has dominated the conversation around college in prison programs for years, in part because it’s a challenge to keep these programs alive. College in prison programs rely on prison administrators to allow them to operate inside correctional facilities.

“A lot of programs interested in ensuring the sustainability, the success or the growth of their program turn to the measures that resonate with the public, and resonate with policymakers and resonate with administrators of departments of corrections,” she said. “So we hear statistics about recidivism all the time.”

Both Ginsburg and Gould point to the failures of the metric. Recidivism rates, they say, don’t capture people who continued their education beyond prison or landed a job since their release.

“They don’t capture people who are homeless. They don’t capture people who have been estranged from their family. They don’t capture people who are depressed or suicidal,” Ginsburg said.

‘You can’t measure how many lives I’ve saved’

The metric doesn’t take into account people like Page, the former EJP student. Page said he learned how to research and think critically while a student in EJP. He also created an anti-violence program with other EJP students.

Page was released from prison in 2014. Now 45, he works at a nonprofit called Contextos. The organization aims to stop violence by helping young people heal from traumatic experiences.

“You can’t measure how many people’s lives I’ve saved, right. Because what my goal is is to stop retaliatory violence. How do you measure that?” Page said.

‘It’s disruptive’

That’s exactly what EJP students, graduates and Robinson, the evaluator, are trying to figure out. For nine months, Illinois Newsroom repeatedly asked for access to Robinson’s evaluation committee meetings with students inside the Danville prison. The Illinois Department of Corrections denied those requests.

Illinois Newsroom requested an interview with an IDOC official. The department denied that request, too.

The Association of State Corrections Administrators connected Illinois Newsroom with the secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, John Wetzel.

Wetzel said he’s a big proponent of education in prison programs.

“I love the concept of looking beyond recidivism, but I’m also someone who’s responsible for a $2.7 billion budget. And folks want to know that they’re getting a return on their investment,” Wetzel said. “I know recidivism isn’t the only measure, but it gets hung around our necks as corrections administrators.”

Wetzel said he’s optimistic that the number of higher education in prison programs will increase. He pointed to the passage of the First Step Act in December — a historic law that reduces federal prison sentences — as evidence that prison reform has bipartisan support.

He hopes federal lawmakers will pass legislation allowing prisoners to once again receive federal Pell Grants to help them pay for a college education behind bars. The 1994 crime bill stripped Pell eligibility from people who were incarcerated.

Both Ginsburg and Gould are concerned, however, that restoring Pell Grants to prisoners could provide a financial incentive for colleges and universities to provide subpar college in prison programs. Unlike students on traditional campuses, Ginsburg said incarcerated students can’t transfer to another university or college.

“They’re not in a position to vote with their feet. They are stuck there,” Ginsburg said.

She hopes the evaluation structure EJP creates will be used as a model by college in prison programs across the country. Ginsburg said if the field can agree generally on what a quality program looks like, that may make it harder for low-quality programs to get a foothold.

Page, however, is worried about the future of EJP — a well-established, long running college in prison program.

“I’ve worried about it from the day it started. Because I understood what it was. It’s disruptive,” he said.

Page said the program encourages students to question everything. He said that’s not what the prison system wants from its population.

While he’s not concerned about the men who are currently enrolled, he is concerned about those just entering the prison system.

“What about the guy that’s getting off the bus right now — 19 years old, 10 years to do in prison. But he hears about this program called EJP. It gives him something to aspire to,” Page said. “I think the door should be open for him.”

Advocates for these programs agree it’s challenging to keep a college in prison program alive. Page, Ginsburg and others say figuring out what that investment of time and money actually does for incarcerated students — beyond whether they return to prison — will hopefully ensure that programs like EJP continue to exist.

Follow Lee Gaines on Twitter: @LeeVGaines

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.