Drought, killer dust storms, torrential downpours, flooding and extreme weather. Illinois, the country’s number one producer of soybeans, and number two producer of corn, has seen it all this year.

Climate change is severely disrupting agriculture, a $19 billion per year industry that is one of the state’s largest. There’s growing recognition, too, of how agribusiness is likely contributing to the problem.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, agricultural production is responsible for about 10% of global warming, with much of that attributable to livestock. In Illinois, with its fertile, black soil created by glacial action, there are 72,000 farms on 27 million acres, three quarters of the state’s land mass.

Change starts with words, and the two phrases making the rounds nationally — “climate smart” and “regenerative farming” — have not quite caught on in rural Illinois. But the actual farming practices that prevent erosion, runoff and carbon emissions, have been practiced for years by early adopting corn and soybean farmers.

“You can’t sit in Washington and tell people how to farm,” said Larry Dallas, who farms about 2,000 acres near Tuscola, and has used conservation practices during his 39 years in business. “There is practicality involved. The technology is out in the field.”

Now the practices are being discussed more widely, not just by tiny organic farmers and true believers, but among the large- and medium-sized growers. WBEZ recently attended a daylong forum sponsored by the Illinois Farm Bureau and talked to farmers about how to farm profitably while trying out a menu of conservation practices. The severe spring drought was still on their minds, as well as an 11 million cubic yard pile of soil dredged out of Lake Decatur along the Sangamon River.

Michelle Carr

She wanted everything to go just right, but one of the worst droughts in Illinois history was not in her game plan. Fortunately, she got the planting done early, and the crop got established before the drought.

“That felt like a win,” Carr said.

She even managed to pull off the neat “double crop” trick of growing wheat over the winter, and harvesting and selling it in the spring before planting soybeans in the same field. The 106 acres of winter wheat also served as a cover crop, helping keep the soil in place and preventing it from blowing or washing away in a bare field for six months.

Cover crops have been used for years, but are planted on less than 5% of farmed acreage in Illinois. Some farmers and agronomists think that the practice of cover cropping holds the most promise for not only preserving soil, but enhancing it naturally, with less fertilizer — and for trapping carbon that would otherwise be released to the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. Carr grows wheat and other cover crops on 35-40% of her land, mostly on the more erodible rolling hills.

“One day I would like to have everything in a cover crop,” Carr said. “I know how important it is. Whether I can economically get there, I don’t know.”

Cover cropping hasn’t been widely adopted in Illinois because it costs money to plant another entire crop, and then to kill the crop before you plant corn or beans in the spring. Cover crops are also tricky to manage, farmers say, and they require more man-hours, different equipment and, most of all, could impair yields on cash crops.

To help with planting barley and rye cover crops, Carr recently paid $10,000 for a used drill planter, including repairs, an item that can cost up to $80,000. “I had to start somewhere,” she said.

Carr, who graduated from Southern Illinois University with a plant and soil science degree, said she attended the recent Farm Bureau field day in Monticello because she wanted to learn more about growing cover crops effectively. Many young farmers like her, she said, have a hunger for updated research and information.

Jake Lieb

Trying new things comes easily to the Lieb brothers, who have posted videos of their fifth-generation farm on YouTube.

For example, with a USDA program that provides cost-sharing assistance for some environmentally friendly practices, the Liebs installed grass waterways and terraces to slow erosion, began no-till farming on some ground (no-till farming reduces wind and water erosion and releases fewer nutrients and carbon into the atmosphere), and now have planted winter cover crops on 600 of the more than 3,400 acres they farm.

“Anything we can do to keep the soil from washing away, or blowing away, and keep our nutrients in the field rather than going downstream we’re wanting to do because fertilizer is very expensive, and you can’t replace the soil,” said Lieb, 41, a graduate of Southern Illinois.

It’s been a learning experience, he added. “When we first got into it, cover crops were not widespread in this particular area. I wasn’t the first one by any means, but there wasn’t a lot of knowledge from fellow farmers that I could ask. Now it’s a little more widespread.”

Jared Gregg

The city just recently spent $100 million dredging 11 million cubic yards of valuable Illinois soil out of its lake in order to make room for more drinking water. Decatur doesn’t want to do that again.

Gregg’s farm is at the top of that watershed, and he wants to be part of the solution. He has already been minimum till and no-till for his soybean crop since 1988. “All of my farms have filter strips to try to mitigate the impact of nutrients entering the watershed.”

Several species of grasses now slow the flow of nutrients from the edge of the field to the drainage ditch. “They can be between 60 and 120 feet wide, and they serve a dual purpose. Not only are they great for nutrient management, but they’re a wonderful place for upland game, wildlife. We don’t mow them.”

Gregg, 39, has also planted 25 acres of wildflowers for pollinators, an activity that the USDA helps pay for. And he just completed a watershed project with USDA assistance. He thinks the billions more earmarked last fall by the federal government to encourage more climate smart agriculture will attract more farmers.

“I have two daughters, I’ve got one that’s 9 and one that’s 4. And I realized that nature is a huge part of this: of farming, protecting nature, protecting not only the soil but the animals and insects that have been here longer than we have and will be here long after we’re gone. It’s not only for me, but for them and their generation.”

This fall, Gregg is going to try a small cover crop.

“Farming always changes, it’s never the same. There’s always something that either we’re fighting or trying to work with or against. The things and practices that my grandfather did I’m not doing, and if he was here today he’d be glad to see that we’re not.”

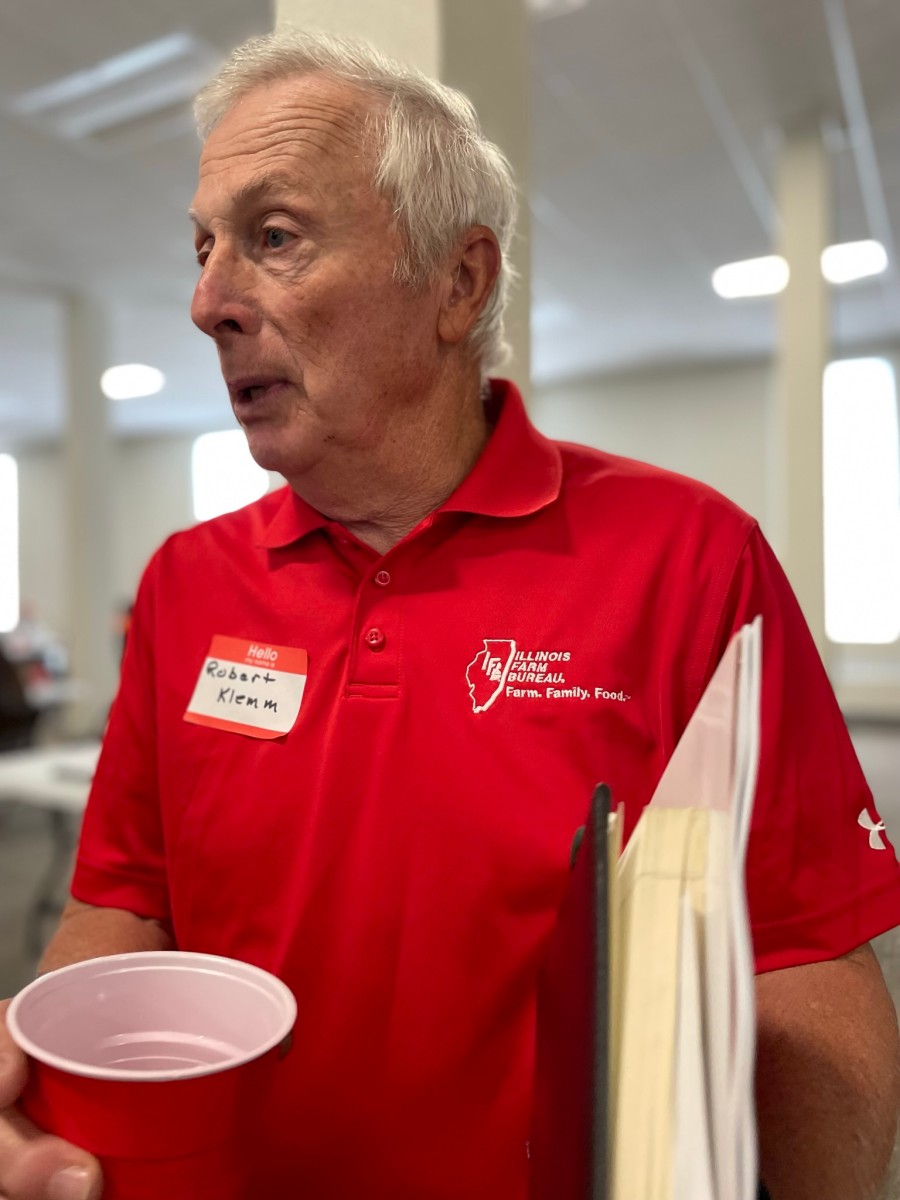

Robert Klemm

“The farm is a centennial farm. My Dad said he wanted to leave the ground in better shape than what my Grandad gave it to him. My son’s farming with me; I have that same goal.”

And yet, he said, farmers have to balance conservation practices with their livelihood.

“Profitability — that’s what puts food on our table. You got to know how can you accommodate to do the practices, and determine what practices are going to be the most beneficial to the land and maintain the profitability. It’s that whole rounded picture that you have got to evaluate.”

Klemm, who graduated from Illinois State, has participated in the USDA cost-sharing programs to install grass waterways, terraces and other projects. But like many other farmers, he has not used cover crops.

“We’ve tinkered around with cover crops just because I think it’s a thing that we need to be evaluating how it might be capable of being used on a larger scale on our farm.”

“It’s not as much as what it could or should be,” Klemm said of the adoption of conservation practices by Illinois farmers. “Part of that is the bottom line.”

Zachary Nauth is a freelance writer who lives in Oak Park.