Update at 4:30 p.m. Tuesday, July 9: all 202 titles removed from the Education Justice Project have been returned to the program’s library inside the Danville Correctional Center, according to EJP staff.

The new director of the Illinois Department of Corrections said during a legislative hearing in Chicago on Monday that the agency plans to revise its policy regarding what books can and cannot enter the prison.

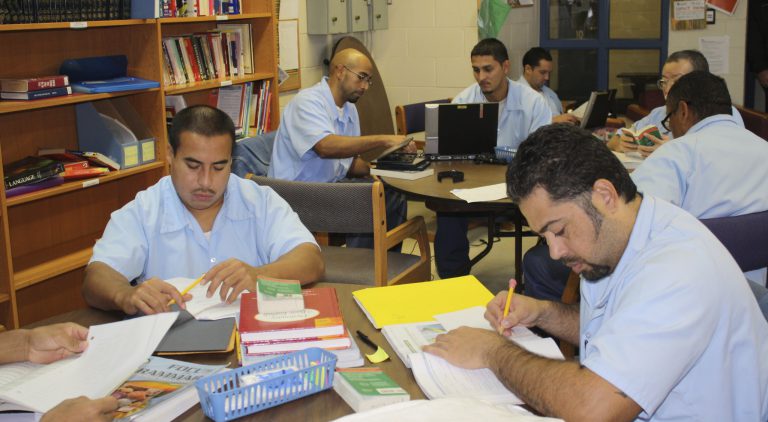

State lawmakers hosted the hearing after Illinois Newsroom reported that Danville Correctional Center officials had removed more than 200 books from a college in prison program’s library inside the facility earlier this year. The books were part of the Education Justice Project’s library — that’s a program that offers University of Illinois classes to men inside the Danville prison.

Many of the removed books deal with race, specifically the history and experiences of African-Americans. Other titles, including “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” were denied entry to the prison.

The EJP program was founded more than a decade ago. The director of EJP, Rebecca Ginsburg, told lawmakers that this level of censorship is unprecedented in the program’s history. She said EJP staff and volunteers received no notification from prison officials about the book removal before or after it occurred. She discovered the books were removed after EJP students told program staff.

Ginsburg also told lawmakers that she was informed by staff at the prison and an IDOC administrator that books on race were removed because they were “divisive.”

She said a Danville prison official told an EJP staff member that “the problem is the racial stuff.”

When asked by Illinois Newsroom in May, the former director of IDOC, John Baldwin, said the books were removed because they weren’t properly reviewed. Emails obtained by Illinois Newsroom, however, indicate that at least some of the books were reviewed and approved to enter the prison.

State Rep. Debbie Meyers-Martin, a Democrat who represents Chicago’s south suburbs, asked Ginsburg during the hearing whether staff at the prison provided any documentation or incidents that would lead them to believe these books should be censored.

“No,” Ginsburg responded. “In response to queries, they were not able to provide any evidence or an example of what was meant by divisive, or in what way there had ever been a history of these books proving divisive.”

The new acting director of IDOC, Rob Jeffreys, did not confirm or deny Ginsburg’s statements.

“I know we’re probably interested in knowing how and why it happened, but I’m more interested in moving forward,” Jeffreys said.

He added that the hearing was being held because, “there was a lack of communication, there’s a lack of expectation. There wasn’t a sound process. And there’s much-needed policy oversight.” Jeffreys was the only IDOC official to testify Monday.

State Rep. Carol Ammons, an Urbana Democrat, who organized the hearing, said lawmakers “need to know what actually happened in this incident.”

But she stopped short of directly asking Jeffreys to address the issue during the hearing, instead saying she hoped he could send her the answer.

Jeffreys said the department would revise its publication review policy, which he said hadn’t changed since 2003.

“That has been my number one thing: to revitalize our current policy creation, review and application,” he said.

Jeffreys also told lawmakers that all but 14 of the removed books were returned to the prison library’s shelves; the outstanding 14 titles would be reviewed further, he said.

‘It just makes me think about slavery’

Alan Mills, executive director of the Chicago-based Uptown People’s Law Center, told state lawmakers during the hearing that “this situation in Danville could easily have been avoided.”

The department’s publication review process applies to books sent directly to inmates inside Illinois prisons, Mills said. It’s unclear whether the policy also applies to programs like EJP.

Regardless, Mills said the policy on the books isn’t being followed.

Mills represents publishers and an author who are suing the department over censorship of reading material in state prisons. The lawsuits were filed last year.

While Mills argued that some books should be banned from prisons, “there needs to be a stated rationale for anybody who decides a book should be censored laying out in specific what in the book is objectionable.”

He said the department should also provide evidence that a book or type of book has caused a problem in the past, and the department should keep reviews of publications in a central location.

“To say we ought to be able to censor things we think are ‘divisive’ because it tells the actual history of African-Americans in this country, that is not only bad policy but it’s also illegal,” Mills said. “The Supreme Court has made it very clear you have to have a legitimate neutral reason to censor something.”

State Rep. Jennifer Gong-Gershowitz agreed. Gong-Gershowitz is a Democrat who represents Chicago’s northern suburbs.

“Regardless of whether it’s associated with an education program, I fail to see how there can be a constitutional justification for banning Frederick Douglass’ autobiography,” she said.

State Rep. LaShawn Ford, a Chicago Democrat, compared the issue to slavery. He said the freedom to read and write allowed slaves to communicate and maintain relationships with family members.

“It just makes me think about slavery… it seems like that’s what’s happening in our state prisons today if we do this type of nonsense,” Ford said.

State Rep. Terri Bryant, a Republican from southern Illinois and a former corrections officer whose district includes seven prisons, said the department also needs to think about security.

She cited a 2009 incident in which a prison librarian was held hostage by an inmate at Pinckneyville Correctional Center. Prison libraries, she said, can be places for incarcerated people to expand their minds, but they’re also “a very dangerous place dependent on who is allowed to be in there on any given day and what the mood of that incarcerated person is.”

‘A recipe for discord’

Jennifer Vollen-Katz, the executive director of the John Howard Association, a non-profit prison watchdog group, said there are two issues at play. First, she said the state lacks a review process that is “accountable, consistent, based on reasonable guidelines that are publicly defined, reviewed by a committee that represents multiple perspectives… and transparent.”

The second issue she said is the censorship of publications.

“When you are in prison you still have First Amendment rights, and it is important we guard those rights,” Vollen-Katz said. “The expansion of the mind and availing oneself of new info might lead to new opportunities and betterment and rehabilitation — all things we seek for people in prison to get from the Illinois Department of Corrections.”

She said the department uses its sweeping authority to determine what can and cannot come in.

“Without making that process clear and consistent and transparent we have a real problem in understanding what’s going on in why some materials come in and others don’t, which is also a recipe for discord,” Vollen-Katz said.

The censorship problem, she said, is best solved with a clear and consistently applied review process that is publicly available.

But several lawmakers appeared averse to passing legislation to mandate change.

State Rep. Norine Hammond, a Republican who represents west-central Illinois, said she believes Jeffreys, the new director of IDOC, brings a “wealth of knowledge” to the position.

“My hope is that we can be your partners,” she said. “We can work together with you and your staff, that you can set up policies that are appropriate and that are followed and at the end of the day we don’t have to legislate this.”

Ammons told Jeffreys she expects to see progress on the censorship issue between now and the start of the fall legislative session.

“I have to bridge the gap, and I’m looking forward to it, between security and programming,” Jeffreys said.

Follow Lee Gaines on Twitter: @LeeVGaines