URBANA – 2022 marks the 100-year anniversary of WILL-AM, the oldest component of Illinois Public Media. The University of Illinois launched the station at a time when the idea of using radio to reach a mass audience was new and cutting edge. There was no FM radio or TV, no internet or social media. The first trans-Atlantic telephone call was five years away.

Throughout the year, we’ll be looking back at this station’s earlier days, and the country’s earlier days, too. But this first article goes back to WILL’s beginning, during the early years of radio broadcasting in the United States.

Our Origins During The “Radio Craze” of the 1920s

If you had a radio from that period, the kind that used more than one knob to tune in a station, it might make a whistling noise as you searched for a broadcast. For University of Michigan media historian Susan Douglas, that sound was part of what made radio listening exciting.

“When you were tuning and trying to go from one station to another, you heard what sounded like occult noises from deep space, from the ether”, said Douglas, using a word that referred poetically to the upper reaches of the sky.

Douglas says that for many Americans in WILL-AM’s first sign-on year, 1922, the sound of a radio being tuned evoked a kind of romantic potential, the potential that you might hear anything from anywhere.

“And back then it was miraculous,” said Douglas. “It was a miracle to people, that you could put some headphones on, and you could hear voices and music from 50 miles away, a hundred miles away.”

There were only a couple of million radios in the US in 1922, and many areas still had no stations of their own. There were no radio networks yet, and radio advertising was still a new and controversial idea.

It was in this setting that the University of Illinois received a license to operate a radio station specifically for broadcasting to a mass audience. The station’s first home was the U of I’s electrical engineering lab. And it was overseen for many years by the campus publicity department.

The Birth of WRM

Josef Wright was the U of I’s publicity director and WILL’s first director of broadcasting from the mid-1920s through the ‘40s. He once spoke with WILL about his memories of the station’s first transmitter and first set of call letters.

“Hugh Brown, a professor of electrical engineering had built a small transmitter of 100 watts or so for an experimental project,” said Wright. “And that was the only thing the university had in the real early days. He dubbed it WRM. Most of us called it the Worm, and he said no, that means ‘we reach millions’.”

Maybe not millions, but WRM did receive its share of mail from DX-ers. The “DX” referred to distance. DX-ers were listeners searching their radio dials for distant stations, and then writing to the stations to let them know they had heard them. Stations typically sent DX-ers a postcard in acknowledgement. No recordings are known to exist of the early broadcasts that those DX-ers heard on WRM. But Susan Douglas says the programming on most university stations in radio’s earliest days, were something of a jumble.

“You might have a lecture on home economics, followed by somebody singing, followed by weather reports, followed by crop reports,” said Douglas. “You know, you didn’t know what you were getting.

“They were terrible at it, until the 1930s,” is Josh Shepperd’s summation of most college and university radio stations during the early years. He’s a media studies professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Shepperd says radio was so new in the 1920s, and so new to university faculty and staff, that things like regular program schedules and effective microphone technique only came gradually. But he says from the 1930s onward, the staff at WRM, which changed its call letters to WILL in 1928, would become a leader in the field of educational broadcasting.

“The University of the Air”

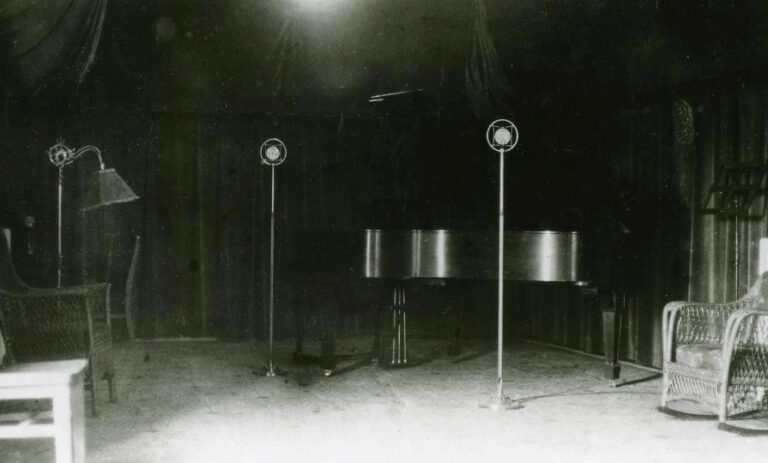

Calling itself ‘the university of the air’, WILL produced programs that ranged from concerts of classical music (performed in the studio and at remote locations on campus) to broadcasts aimed at farm families, to Illini ball games.

Josh Shepperd says WILL, along with key U of I communications faculty such as Wilbur Schramm and Dallas Walker Smythe did important work in developing educational broadcasting both at the local and national level.

“And they really, really cared about this work,” said Shepperd. “There was almost no incentive, there was almost no money for it. But the practitioners that coalesced around Urbana-Champaign really had this vision that vision that media could serve public amelioration of access to democracy, education, equity, all these kinds of things.”

From “Educational” to “Public”

In 1972, WILL looked back in a special 50th anniversary broadcast, “The Sounds of Sign-On”, which it also issued as a record album. The program looked back on the wide range of local programming the station had produced over the years. Left unmentioned was WILL’s contributions to educational broadcasting on a national basis, including the formational conferences it held with other broadcasters, and the early national program service it operated in the 1950s.

But by 1972, educational broadcasting, now known as public broadcasting, had grown. WILL was also operating a TV station, airing programs from the fledgling PBS network, such as “Sesame Street” and “Masterpiece Theatre”. And WILL’s sister station, WILL-FM, was airing a new daily news program called “All Things Considered”, from a new network known as National Public Radio.

As WILL observes its 100-year anniversary in 2022, we’ll look back at the station’s history again, with special features throughout the year, as well as mentions in our Illinois History Minutes. More details are outlined in the WILL timeline on the Illinois Public Media website. As for the future of WILL and its parent organization, Illinois Public Media, we’ll see what comes out of the ether.

Also in the WILL at 100 series: when Langston Hughes read his poetry at the University of Illinois.