URBANA – WILL-AM 580 turned 100 years old this year. And classical music has been a part of our programming from the very beginning. Classical music by people of color, however, did not always get much attention.

Roger Cooper, a longtime classical music host at WILL-FM 90.9, filled the gap with a series of programs celebrating Black performers and composers.

The program, titled “Classically Black” had its origins in the late 1980s. Cooper, a classical host at WILL Radio since 1978, developed “Classically Black” as an annual program that aired during Black History Month in February.

The first “Classically Black” broadcasts featured music by various Black performers and composers. But by the early 1990s, each annual program was devoted to a particular performer, composer, or related group of composers.

Warfield’s Contribution

One of the early programs showcased William Warfield. The bass-baritone, who died in 2002, was perhaps best known for singing “Old Man River” in the 1951 movie version of the musical “Show Boat”. But on “Classically Black”, Cooper provided a larger selection of his work, extending to Warfield’s performances of baroque music by Heinrich Schutz and George Frideric Handel.

Warfield had played a role in Roger Cooper’s own understanding of the role of Black artists in classical music. He fell in love with classical music at an early age, while growing up in Evansville, Indiana. But he found little support at home, where his family’s conservative religious background discouraged most music outside of church. And Cooper says that as a child, he didn’t think that people like him had much involvement in classical music at all.

“I mean, I didn’t know Black people did classical music,” said Cooper, laughing. “You know, they wrote classical music — what? You know, my experience of classical music with Blacks was, you know, the radio, and jazz, the occasional artist that you might hear on a program, but it was always a big rarity.”

Nevertheless, Cooper knew about William Warfield. He had watched him portray “The Lord” in a 1950s “Hallmark Hall of Fame” production of Marc Connelly’s play “The Green Pastures”. The telecast (produced in 1957 and again with most of the same cast in 1959) gave Warfield his biggest television role.

Later, Cooper saw Warfield in concert. The singer performed in Evansville in the 1960s, when Cooper was an undergraduate student at Evansville College (now the University of Evansville). He says people at his school talked about Warfield’s Evansville concert for a couple of years afterwards.

“He had a magnetism to the audience that sounded, it seemed like he was just singing to you, personally, nobody else, just you,” said Cooper of Warfield’s performance. “And it was the most extraordinarily beautiful voice, unlike any voice I’d ever heard.”

After graduating from Evansville College, Cooper taught music at the elementary school level. He then enrolled at the University of Illinois as a graduate student, studying voice with an eye towards becoming a voice teacher. While there, Warfield joined the university’s music faculty, and Cooper studied under him for a time.

By the time of his appearance on “Classically Black”, Warfield was a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois. In fact, Cooper had studied under him as a graduate student. Despite receiving a master’s degree from the University of Illinois, Cooper did not pursue a music career. He had already begun working at WILL Radio at the university and would stay with the station for 30 years.

Over the course of his time with WILL, Cooper hosted classical music in the evening, morning, and afternoon, and also prepared classical music for others to host (he says Focus 580 host David Inge was particularly good as a classical announcer). He also announced broadcasts of local classical music performances, including live broadcasts, such as WILL-FM’s “Second Sunday” concerts.

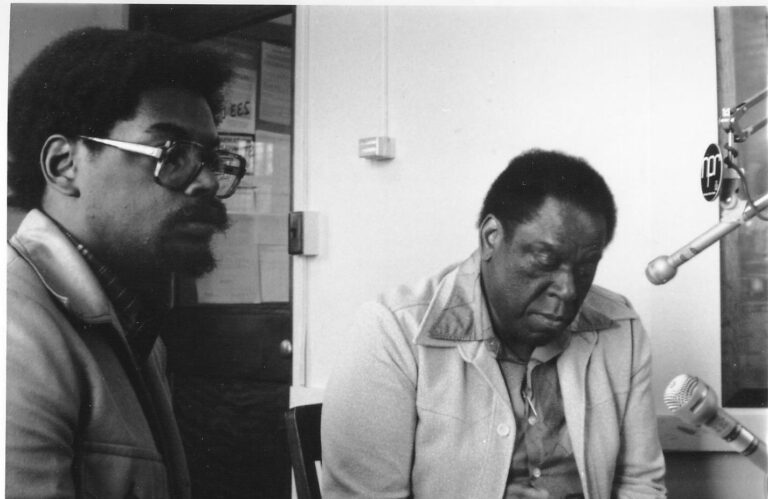

Cooper produced an annual “Classically Black” program for WILL-FM (and in some years, WILL-AM) in addition to those regular duties. Each program was extensively researched, and in the case of the 1993 William Warfield program, included an interview with the artist.

For that program, Cooper asked Warfield about his performance in Leonard Bernstein’s unconventional 1956 presentation of Handel’s “Messiah” oratorio with the New York Philharmonic and the Westminster Choir. At that concert, later released as a recording, Warfield sang the aria “Why do the people rage so furiously together”, at what at the time was considered an unusually fast tempo.

“How did you and Mr. Bernstein arrive at this breakneck speed?”, Cooper asked Warfield on “Classically Black”.

“He did!” said Warfield. “I showed up for rehearsal at Carnegie, and he started out —,” here, Warfield hummed Handel’s melody at the fast tempo that Bernstein requested.

“I said, ‘I don’t do it that fast,’” said Warfield. “He said, ‘Oh but I want – the strings have to rage, this is about war, I want to be able to rage with the strings’. And so I said, ‘OK, let’s try it’. He said, ‘try it, try it, it’ll work, it’ll work’. And sure enough, I did, I just whoomp! And off it went.”

Warfield was also interviewed for other Classically Black programs showcasing African-American singers he knew or had known, including Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Warfield’s former wife (and “Porgy and Bess” performing partner) Leontyne Price. Cooper remembers him as a “treasure trove” of information about Black artists in classical music.

“He knew everybody,” said Cooper of Warfield. “He knew all of the Black classical performers, who were still living and performing, and some of those who had passed on. And so, he could speak of them in first person: ‘I knew him, and this is what they thought’. And it was great.”

William Grant Still and Others

In addition to Warfield, Cooper turned to music historians and other experts, for help in telling the stories of Black performers and composers. Early “Classically Black” programs featured the late Rosemary Stevenson as both a researcher and a guest, using expertise she had gained while compiling a bibliography of materials on African-Americans in classical music at the University of Illinois.

In the case of Cooper’s 1995 program about 20th century Black composer William Grant Still, he turned to a family member.

Still was known for his Afro-American Symphony, and other works influenced by Black American musical traditions. For that program, Cooper interviewed Still’s daughter, Judith Ann Still.

“Well, he was a gentle, loving man,” the younger Still told Cooper. “Very much dedicated to his work, so we didn’t see him a lot during the day when he was composing. He would emerge in the evening and read bedtime stories.

Cooper traces his connection to Judith Ann Still to an earlier “Classically Black” broadcast, where he played one of Still’s choral works.

“And it concluded with an anthem by William Grant Still, called ‘All That I Am’ that got to be very, very popular,” said Cooper. “We had a lot of people call in, wanting to know what it was, how could they obtain copies of it, people looking for the sheet music. His daughter called me to say thank you for playing that and telling me what an impact it had had on the ordering of the music and stuff, a lot of church choirs were doing it.”

Other “Classically Black” programs showcased the music of pianist Andre Watts, jazz pianist/bandleader and composer Duke Ellington (focusing on his ambitious extended compositions), African-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 20th century composer Adolphus Hailstork and the “Creole Romantics”, a group of 19th century composers with roots in New Orleans (Edmund Dede, Charles Lucien Lambert and Louis Moreau Gottschalk,).

“Classically Black” also reached a national audience. The annual programs were picked up by American Public Radio, later Public Radio International, for broadcast on other public radio stations around the country.

Showcasing Black Artists in Classical Music

Cooper says “Classically Black” was meant to showcase the best-known Black performers and composers in the world of classical music. And he says, compared to when the program began, those artists are better represented in the classical music world today. But he says many still deserve more attention, such as Black composers from past eras — among them, the Black baroque composer Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, who Cooper showcased in one of the later “Classically Black” programs.

“Nobody had ever heard of a Black Baroque composer or a Black classical composer. Or a Black person who was a friend to one of the major composers, like (African-British violinist) George Bridgetower and Beethoven. So I think like everything else, things have improved, but there’s still a ways to go.”

Roger Cooper retired from WILL-FM in 2008, having produced his last “Classically Black” program in 2006 — that one showcasing 20th century composer and pianist Florence Beatrice Price. But “Classically Black” is still on the air, with the older programs being rebroadcast every year during Black History Month on WILL-FM.